Concepts for the Study of Latin

Nouns and Related Concerns

Don't let confusion seize you.

|

Concepts for the Study of LatinNouns and Related Concerns |

Don't let confusion seize you. |

In order to work with nouns in Latin, you need to know not only the noun's meaning but also its gender, case, and number. The activity of generating noun-forms is called declension; the patterns in which different nouns generate their forms are also called declensions.

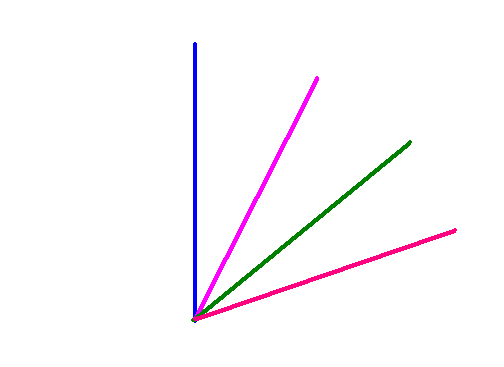

Cases - sorting out noun-functions:| The different forms nouns take in Latin in order to show their function in a phrase or sentence

are called cases. The term comes from Latin casus, a "falling," with the idea that the

noun changes its form slightly but still names the same thing,

still remains essentially the same noun, like a stick "falling" down from the vertical. The same image gives

rise to the term oblique cases for everthing except the form that's used for the subject,

since they're the slanty ones where the stick is tipped part-way.

English uses a special case-form to show possession ("the log's bump"), but mostly relies on other features of language to indicate grammatical function. Latin uses case-forms much more systematically. If you recognize the case in which a word is appearing, and if you know what sorts of functions the cases can perform in a sentence, you're most of the way to understanding what is being said. The general kinds of function designated by the different case-forms in Latin, and the names of the cases, are as follows: |

|

| subject of sentence: the thing a sentence is telling you something about

("The subject is what grammarians call the sentence's topic"; see further in the

discussion of predicates);

anything being identified with the subject ("Colorful flowers bloom"; "The flowers are lovely.") |

"nominative" comes from the Latin word for "name": this case "names" the thing | |

noun-to-noun relationships English

often expresses with the preposition "of", such as possession ("the wisdom of my

teacher"  ), partition ("many

of the students"), description ("a person of

interest"), etc. ), partition ("many

of the students"), description ("a person of

interest"), etc. |

"genitive" comes from the Latin word for "birth": this case puts a noun in a "familial" relationship to another noun | |

| indirect relationships, such as indirect object ("Show me the way;" "Show the way to me.") | "dative" comes from the Latin word for "give", an easy example of situations involving an indirect object | |

| direct object ("An action directly affects the direct object.");

in Latin, with prepositions indicating dynamic position ("between you and me") |

"accusative" comes from the Latin word for "call to account", an instance when attention is focused directly on that object | |

various adverbial ideas, in three main categories:

|

"ablative" comes from the Latin word for "take away": this case is named for its separative function,

but in Latin the form for separative ideas mostly took over instrumental and locational functions too

some Latin nouns, mostly proper names of places, retain a separate locative case for place-where ideas ("at home") |

|

| direct address (not really part of the rest of the sentence, but a sort of address-label affixed to it: "Hey, you!") | "vocative" comes from the Latin word for "call": this case "calls" the sentence to someone's attention |

Declensions - sorting out noun-forms:

|

"the bump grows on the log" : "the log grows on the bump" |  |

| Many languages recognize a certain something about nouns, beyond their capacity to name things. It's conventional to refer to this quality as gender, even though it doesn't always or necessarily correlate with obvious examples of beings with gender-differences between them, like female and male people. Also, users of a language frequently speak as if gender inhered in the thing the noun names - but the same thing, and even the same word, can be different grammatical genders in different languages: for example, "auto", meaning a motor-propelled 4-wheeled vehicle a person can drive while sitting inside of it, is neuter in English and German, feminine in French, and masculine in Spanish. |   |

Very nearly almost entirely without exception, a given noun in Latin has one gender and sticks with it all the time. Gender should be learned as a property of the word.

Latin recognizes "natural gender": nouns that name female beings are feminine and nouns that name male beings are masculine. Feminine or else masculine, however, is as much flexibility in reference to the gender of human beings as Latin is equipped to handle: in instances of gender-fluidity, switch back and forth between feminine and masculine genders for the same grammatical number as the number of persons you are discussing (Latin does not do gender-neutral singular "they/them/their"). Many Latin words that wouldn't strike a habitual English-speaker as having a natural gender are masculine or feminine, while many others are neuter. Again, you have to learn the gender as a property of the word.

Gender does not map entirely evenly onto the declension-system, but some general tendencies appear:

| first declension | second declension | third declension | fourth declension | fifth declension |

| mostly feminine, except nouns naming people Romans typically assumed would be male, which are masculine, like agricola, "farmer" | mostly masculine, except nouns naming woody plants, which are feminine, like fagus, "beech-tree"; additionally, there's a sub-set of neuters | masculine, feminine, and neuter nouns all occur | mostly masculine, except feminine manus, "hand"; additionally, there's a small sub-set of neuters | mostly feminine, except that dies, "day", is usually masculine |

Neuter nouns of a given declension (second, third, or fourth) follow the same declension-pattern as the masculine or feminine nouns of that declension, except as covered by the Two Rules of Neuters:

beech beech

beeches beeches

|

How many items are you contemplating?

English recognizes the difference between singular (just one) and plural (more than one). The quality in which the difference exists is grammatical number. Latin mostly distinguishes between just-one, singular, and more-than-one, plural. As English mostly does (though usually not with sheep, for instance), Latin marks a plural with a different ending from the same word in the same case in the singular. Two words in common use in Latin use forms in a grammatical number that means specifically "there's two of them": the dual. (Both words designate "two-ness": the adjectives for "two" and for "both". But the nouns described as being "two" use the same plural form you'd use with a higher number, because only the two dual adjectives use the dual form: una fagus, "one beech-tree", singulars; duae fagi, "two beech-trees", dual + plural; tres fagi, "three beech-trees", plurals). |

The Inescapable Fact of Adjectives, at least as far as Latin is concerned, is that adjectives describe nouns. Therefore, adjectives have the same characteristics as nouns, gender, case, and number, and therefore these links take you back up to the section concerned with nouns. Likewise, the activity of generating adjective-forms is called declension and the patterns in which different adjectives generate their forms are also called declensions. In fact, most adjectives belong to the first-and-second declensions and to the third declension, as the declensions are known among nouns. The following sections discuss concerns specifically of adjectives:

The Agreement of Adjectives: |

Adjectives describe nouns. In Latin,

an adjective shows which particular noun it's describing by fitting it exactly,

like a glove to a hand or a mirror-image to its original,

by matching it in all the characteristics that count:

for Latin adjectives and nouns, in gender,

case, and number.

The dual number necessitates a trivial exception to this principle: when you've got "two" of something, or are talking about "both" of two things, use the dual of that specialized adjective with the plural of the noun, while gender and case agree as usual: thus for example, duae fagi, "two beech-trees" (first-declension feminine nominative dual + second-declension feminine nominative plural). |

Most Latin adjectives belong either to the first-and-second declensions or to the third declension (the few irregular adjectives we'll deal with separately):

| first-and-second declension adjectives | third declension adjectives |

|

|

|

Degree is the technical term for how intensely the adjective describes the noun it's talking about.

|

Substantive Use of Adjectives:

Because adjectives describe nouns, it is possible to use an

adjective by itself and have it pick up reference to the appropriate noun from context.

English occasionally uses this capability, as in, "Will you give me three brown M&Ms for a green?"

|  |

Pronouns substitute for nouns. Concerns of gender, case, and number are in principle the same for pronouns in Latin as for nouns, and pronouns like nouns generate their case/number forms by declining (they use pronoun-specific forms, though, not the declension-patterns of regular nouns).

|

|

| Latin has separate words, true pronouns, that are used exclusively to indicate person and number in the

first and second persons, singular and plural (I/we, you/you). The third person is covered by a weak

demonstrative used substantively, "the particular [neuter,

nominative, singular]" = "it" (thing, subject), "the particular [feminine, accusative, plural]" = "them" (women,

direct object), etc.

Remember, Latin can use all its adjectives substantively, so they can be used as if they were pronouns too. |

|

|

Demonstratives "point out" entities: "point out" is what the Latin word means that the term "demonstrative"

comes from.

Demonstratives are really adjectives, since you can always use them with a noun expressed, as in "That Girl". But many English speakers use demonstratives substantively and get into the habit of calling them pronouns, so they're included under this heading. Latin can use all its adjectives substantively, so demonstratives have nothing special going for them in Latin in that regard. |

English distinguishes two different degrees of remoteness with its demonstratives. Latin distinguishes those two and an intermediate degree in between them, and also a weak demonstrative that doesn't designate a level of remoteness for the entity it's pointing out. The weak demonstrative signals only the idea that the entity it marks is being singled out as-opposed-to anything else. The weak demonstrative is most often used substantively, to single out otherwise unmarked entities where English would use the personal pronouns of the third person, but it can be used adjectivally with noun expressed, too.

| Most Present / Least Remote | Intermediately Present / Remote | Least Present / Most Remote | Weak Demonstrative |

| "this" / "these" [right here by me] | (no idiomatic English equivalent) "this/that [over by you]" |

"that" / "those" [way over there by them] | (no idiomatic English equivalent) "the particular" |

| hic, haec, hoc | iste, ista, istud | ille, illa, illud | is, ea, id |

Interrogative pronouns ask for identity: in English, "who"/"whom"/"whose" for people, "what" for things.

Latin possesses

|

|

|

Sometimes you want to be vague.

Latin possesses pronouns and adjectives designating several kinds of indefiniteness.

Most, but not all, of the forms are the same for each pronoun-adjective pair.

|

Grammatical reflection occurs when an entity within the

predicate of a sentence is the

same entity as the subject of the sentence.

|

|

fortuitous pun |

It's not really terribly perilous, but a few points are worth watching out for.

|

When you have an idea in the main sentence to which you want to go back and add an extra clause of information,

you need a word like "which" that can pick up reference to the idea in the main sentence, in order to attach them:

the relative makes that connection. Most relatives are adjectives.

|

|

| Anything that has, or appears to have, or has the potential to have, or appears to have the potential to have,

some kind of existence is a substantive. The class of substantives includes whatever nouns

have the potential to name. The term comes from a Latin word for "exist".

Substantives can be represented in Latin by

|

|

Latin prepositions govern either the accusative or the ablative case. A few Latin prepositions can govern both accusatives and ablatives, but they mean different things when they use one case or the other: they describe different relationships. Think in terms of how the idea works that the words are describing, in order to avoid confusion.

| prepositions that govern the ACCUSATIVE | prepositions that govern the ABLATIVE | |||

| describe relationships of dynamic placement | describe relationships of separation, instrumentality, or static placement | |||

| such as "toward," "into", "opposite," "before", "after" | such as

|

| Introduction to grammatical concepts | Verbs and related concepts |

| Loyola Homepage | Department of Classical Studies | Find Loyolans | Loyola Site Index |

Revised 16 November 2018 by

jlong1@luc.edu

http://www.luc.edu/classicalstudies/